From identifying new species of marine life to revealing the scale of plastics pollution in our oceans, Newcastle University researchers are advancing knowledge of our marine environment as well as threats to its very existence.

Read on below to learn more about our discoveries, the threats we're facing and what we're doing at Newcastle University to drive positive change.

New underwater discoveries

Two new species of the rarely seen six-gilled sawsharks were found in the West Indian Ocean by an international team of marine scientists. The newly discovered Pliotrema kajae and Pliotrema annae – affectionately known as Kaja’s and Anna’s six-gill sawsharks - were discovered during research investigating small-scale fisheries operating off the coasts of Madagascar and Zanzibar.

Radiograph of a newly discovered species of six-gill sawshark

Both new species differ from the only previously known six-gill species in the position of their barbels - whisker-like sensory organs around the shark’s mouth which help the shark detect its prey. Living on a diet of fish, crustaceans and squid, sawsharks use their serrated snout to kill their prey. Fast movement of the snout from side to side cuts the prey into fine pieces to allow it to be easily swallowed. Found mainly in the temperate waters of all three major oceans, the number of sawsharks has declined in the past couple of decades due to commercial fishing.

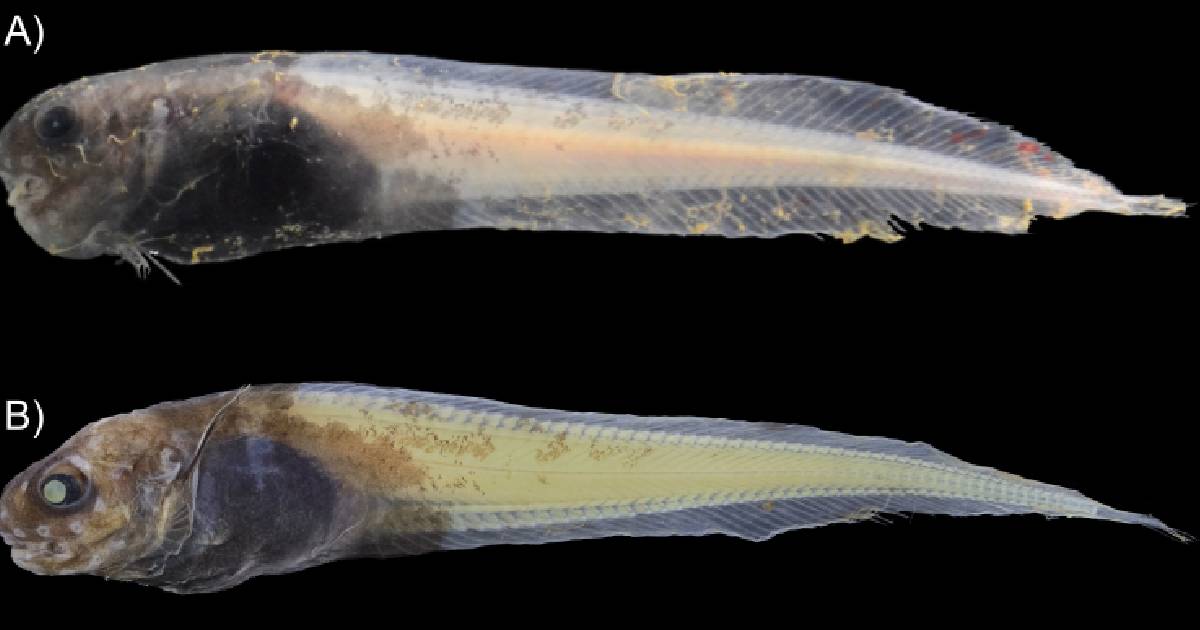

Paraliparis selti - photo credit Thom Linley

In the ocean's mysterious hadal zone, extending beyond a depth of 6,000 metres, we've found a new snailfish that's helping scientists understand life in the ultra-deep. The new species has been called Paraliparis selti, which means blue in the Kunza language of the indigenous peoples of the Atacama Desert.

Closer to home, a grey seal has been captured on camera for the very first time clapping its flippers underwater to communicate. Recorded off the Farne Islands, Dr Ben Burville filmed the event after trying for 17 years to film a seal producing the gunshot-like ‘crack!’ sound that they make underwater during the breeding season.

Used by bull seals as a sign of strength to ward off competitors and attract potential mates, the loud high-frequency noise of the clap cuts through background noise, sending out a clear signal to any other seals in the area. Previously believed to be a vocal sound – like the calls and whistles produced by many marine mammals – this new underwater footage clearly shows a male grey seal repeatedly clapping its flippers to produce the loud noise.

Threats to our oceans

However, not every underwater discovery made by Newcastle University researchers is welcome news.

Our research has also discovered the concerning presence of plastic in deep-sea species in the deepest places on earth. Researchers discovered a deep-sea amphipod – informally referred to as a “hopper” – which contained traces of plastic in the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench between Japan and the Philippines.

The researchers officially named the species Eurythenes plasticus in reference to the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) found in its body. PET is a substance found in a variety of commonly used household items and because it cannot be recycled, it is often burned or dumped at repositories. From there, it finds its way into rivers and, ultimately, into the ocean where it breaks apart into micro plastics and spreads through the ocean where it is ingested by marine animals such as the “hopper”.

This alarming discovery is the latest in the plastic crisis. As Dr Alan Jamieson, Senior Lecturer in Marine Ecology at Newcastle University and head of the research mission, explains “We decided on the name Eurythenes plasticus as we wanted to highlight the fact that we need to take immediate action to stop the deluge of plastic waste into our oceans.”

Eurythenes plasticus with a microfibre highlighted

Saving our oceans

In addition to highlighting the threats to our oceans and ecosystems, our academics are collaborating with industry and academic partners to reduce the impact we're having on our oceans.

Tackling microfibres

We're finding ways to reduce the number of plastic microfibres found in the ocean – millions of which are shed when we wash clothes that contain materials such as nylon, polyester and acrylic. Given their small size, they drain out of our washing machines and can ultimately enter the marine environment.

New research has shown that it is the volume of water used during the wash cycle, rather than the spinning action of the washing machine, which is the key factor in the release of these microfibres. By ditching the delicate wash cycle, we can reduce our plastic footprint and protect our oceans. Working with Procter & Gamble, the team found that the higher the volume of water, the more fibres were released, regardless of the speed and abrasive forces of the washing machine.

Our academics also discovered that an enzyme released by bacteria living on seaweed can revolutionise the way we wash. A powerful, new type of natural cleaner, the enzyme breaks down sticky modules. Working again with Procter & Gamble, the team have demonstrated that it could be used to develop more sustainable laundry detergents that work efficiently and effectively at low temperatures, ultimately protecting the environment.

Newcastle University researchers have discovered an enzyme living on seaweed that could make laundry more eco-friendly

Protecting coral reefs

An international collaboration led by Newcastle University and James Cook University, Australia, launched a new resource to help understand when corals reproduce. The Coral Spawning Database provides more than forty years’ worth of information about coral spawning and provides a crucial opportunity to preserve these remarkable and important ecosystems.

Coral reefs are one of the most species-rich marine ecosystems on the planet and provide enormous societal benefits such as food, tourism and coastal protection. However, they are in sharp decline due to overfishing, pollution and warming seas caused by climate change. Successful reproduction is one of the main ways that reefs can recover naturally from human disturbances.

Montastraea spawning - photo credit Dr James Guest

The open data can be used by scientists and conservationists to better understand the environmental cues that influence when coral species spawn, including temperature, daylight patterns and the lunar cycle. It will also provide an important baseline against which to evaluate future changes in regional and global patterns of spawning times or seasonality associated with climate change.

Exposed corals

Marine heat waves have decimated corals in recent years, and the future looks bleak for tropical reefs if the pace of climate change continues at current rates.

A new study has investigated how much heat stress corals can cope with and how much this varies from one coral to another. Understanding corals' resilience - and its variation within one reef - is critical as it provides insights into how we can help corals adapt, as our planet continues to warm.

The team from the Coralassist Lab at Newcastle University and the Palau International Coral Reef Center exposed corals - taken from a single reef - to an experimental marine heatwave. Remarkably, they found that double the heat stress dosage was required to induce bleaching and mortality in the most-tolerant 10%, compared to the least-tolerant 10%.

They then used future projections of sea surface temperature data from global climate models to contextualise how this variability of coral heat tolerance could influence future mass bleaching under climate change and specifically ocean warming.

You might also be interested in:

- Discover how clownfish grow to match their environments

- Explore how we're working to preserve and protect our coral reefs

- Our research towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals

- Learn more about our One Planet work

- Read about our Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Engineering

We're changing the world with our research. Sign up for our newsletter below, and we'll keep you updated with our latest discoveries.