A newly discovered small blue fish is answering big questions about the deep

11 November 2022 | By: Thom Linley | 6 min read

In the ocean’s mysterious hadal zone, extending beyond a depth of 6,000 metres, we’ve found a new snailfish that’s helping scientists understand life in the ultra-deep.

We caught up with Newcastle University’s Visiting Researcher and lead author, Dr Thom Linley, who, under the leadership of Prof Alan Jamieson, was part of the expedition to the Pacific Ocean that discovered this new, deep-sea fish.

Firstly, tell us more about this discovery.

In 2018, off the coast of Chile, a group of international scientists were brought together by the HADES-ERC project. Aboard the German research vessel RV Sonne they explored the Atacama Trench; a vast, deep underwater valley running along the west coast of South America. It was in this ‘hadal’ zone of the ocean where a remarkable discovery was made - three new species of snailfish were found.

Video from the 2018 expedition: Newcastle University discover new species from the extreme depths of the Pacific

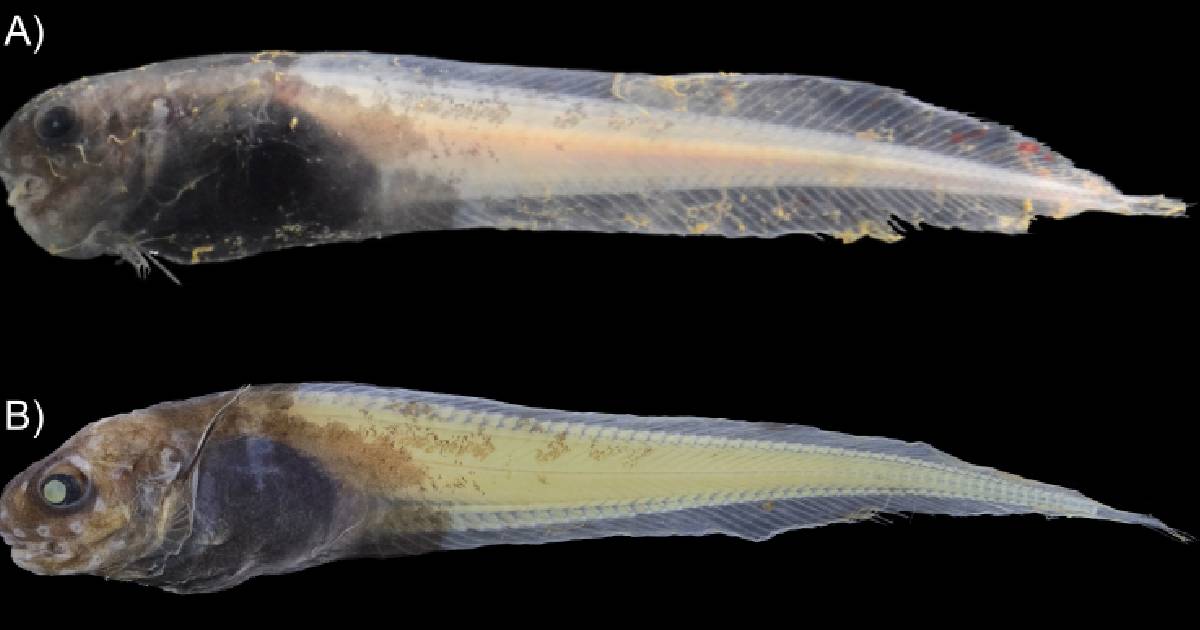

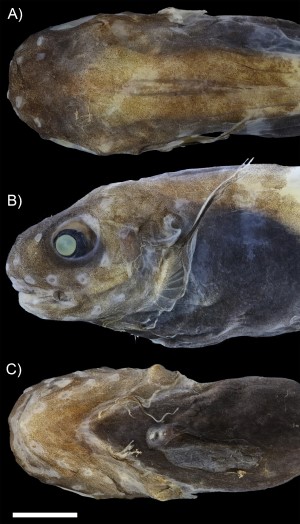

One didn’t look like the other hadal snailfish we had studied. It was a striking blue colour with large eyes, spotted between about 6,000 to 7,600m deep.

The team visited the Natural History Museum in London to use a 3D x-ray technique, called microcomputed tomography (micro CT), and worked with Drs Heather Ritchie (JAMSTEC) and Johanna Weston (WHOI) on genetic barcoding to see where the new species fitted within the snailfish family. We also worked with long-term collaborator Mackenzie Gerringer (SUNY Geneseo) and Jhoann Canto-Hernández (Chile Natural History Museum) to scrutinise the shape (morphology) of the species to look for similarities with other known species.

Surprisingly, the results showed that this blue snailfish belonged to the biological classification called Paraliparis, abundant in the Southern Ocean of the Antarctic, but rarely deeper than 2,000m. This was the first time a member of this genus had been found in the hadal zone.

How did you go about naming this new discovery?

The new species has been called Paraliparis selti, which means blue in the Kunza language of the indigenous peoples of the Atacama Desert.

The process of naming a new species is complex. Even beyond all the biological detail, it’s a really strict process.

It feels more legal than scientific – it’s like you’re patenting an invention, you have to prove how it is different from everything else.

All the rules are amassed in The Code, by The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN).

It also has to go through peer review like any other scientific publication.

As you can imagine, there’s a lag between that thrilling moment of seeing something, knowing that it is new and significant, and doing all the paperwork!

Image: Paraliparis selti, Thom Linley

What is significant about the recent findings?

Firstly, I love to show people that the world’s deepest fishes are actually pretty cute!

There is something special about the snailfish family of fishes (Liparidae). They seem uniquely suited to colonise the deepest places in the ocean, the hadal zone. They thrive at depths beyond other fish.

As the vertebrate champions of this deep zone, we currently think there are roughly 15 species endemic to the hadal trenches around the world. Many trenches have one or as many as three hadal snailfishes (like the Atacama) living in them, deeper than any other type of fish. They are almost always found only in one trench. All the super deep species that we currently have data for seem to be from the same lineage - until now.

Paraliparis selti is a separate colonisation of the hadal zone. We’ve been wondering for some time just what makes this type of fish so good at living deep. Maybe it was a series of lucky accidents, a chance fluke that happened in one lineage. Finding this new species tells us that it’s bigger than that. Lightning struck twice and there is something special about this family. We can now look for similarities between the two lineages to reveal what the secret is to going so deep.

What’s the hadal environment like?

As air-breathing mammals, we do a terrible job at understanding the deep sea. Technically, it starts at 200 m depth, but goes to almost 11km down. It covers the majority of the planet and we stick it all in the same box and call it weird. The numbers don’t lie though, this is a deep-sea planet and we are the weird ones.

The hadal environment is a fascinating one. Most are at the deep subduction trenches – where two tectonic plates collide and one buckles and gets pushed under the other. This creates the deepest places on earth. They are isolated areas accounting for just 1% of the ocean, but represent 45% of its depth range.

The pressure is enormous of course, but it is also cold, dark and seismically active – it’s an extremely harsh environment. But, it has its advantages too, food is less scarce in comparison to the open abyssal plains that make up much of the planet.

Why is deep water exploration so important?

The deep sea sounds like something far away and separate, so why bother exploring it? But it makes up the majority of our planet. It is the largest habitat on earth. We can’t say we understand our planet and how its processes work if we take a totally human-centric view of it. This isn’t just a blue planet, it is a deep-sea planet by majority.

Does understanding deep sea help humans? Do we effect it?

We absolutely affect the deep sea. Plastics, persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and other rubbish are found in abundance.

As for what it could do for us: due to its massive size, the processes of the deep sea affect our whole planet. We cannot accurately predict what the future may hold for us before we have an accurate understanding of how the deep sea works: moving carbon, heat and oxygen around our planet.

On a more specific level, the deep sea is one of the best contenders for future drugs and antibiotics.

How do you explore the deep sea?

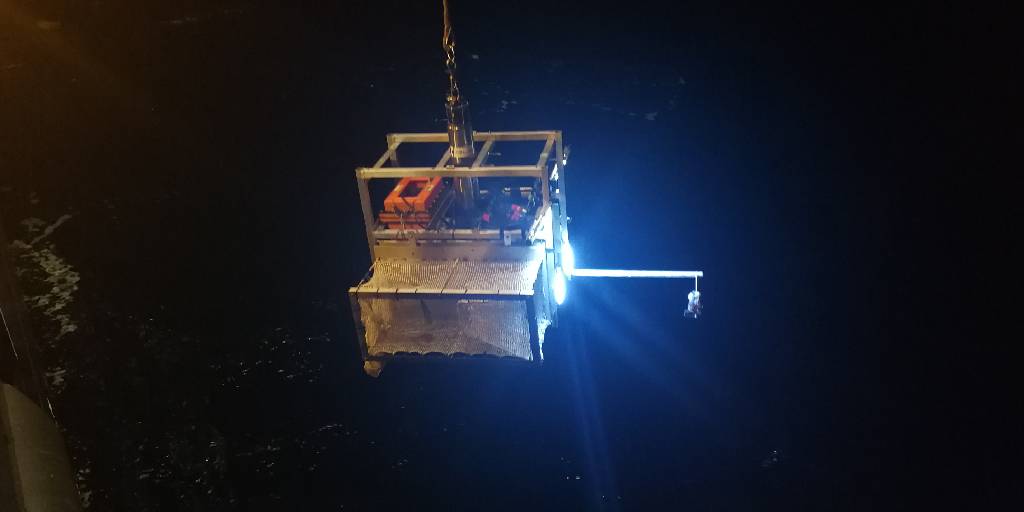

Deep sea exploration has parallels with space exploration, in fact, NASA has started working with deep-sea scientists as we face a lot of the same problems. We have a two-part episode about it in our Deep-Sea Podcast. The biggest challenge is of course the pressure, our equipment needs to withstand the extreme forces down there, something in the region of an African bull elephant standing on your thumbnail!

It is also very difficult to send something down on a cable, it would take an enormous vessel to handle that much cable. 10 km of cable hanging straight down starts to act differently too, stretching and flexing, it soon becomes heavier than the thing you’re lowering and can even overtake it. It also leaves the vessel very vulnerable.

Designed and developed by Prof Alan Jamieson and myself at Newcastle University, free-falling landers don’t need to be lowered from a ship. We drop them from the surface, they fall to the seabed, perform a pre-programmed task and then drop a weight to come back to the surface. We use bait to gather the sparse deep-sea creatures around cameras and traps. We are usually at sea for around three to six weeks for one of these expeditions.

Image: A free-falling lander, Thom Linley

What does the future hold for ocean exploration?

Technology is getting better and cheaper. More people have access to the deep sea than ever before. People are starting to feel that the deep sea is part of their planet, not some strange other world.

At the moment we are only visitors, we see glimpses of exciting things. As we get more eyes down there and gather more data, we are going to see more and more behaviour we’ve been missing. We know what a lot of these animals look like dead, but we know very little about how they live their lives. The future will change this.

How did you end up looking into the deepest parts of the world’s oceans?

I always wanted to work with fish. I wish I had a better explanation, but I never really felt like I had much choice. I had a passion for conservation and wanting to understand fish more. I thought they had a bad reputation, they were seen as these mindless automatons. None are more maligned than deep-sea fish.

They are not alien monsters who look the way they do just to upset us. Everything about them is there for a reason and they don’t even look how we think.

I encourage everyone to look up what a blobfish is meant to look like. A lot of our ideas about deep-sea fish are the result of things we do to them. If we were dragged to where they live then we wouldn’t look very good in photos either!

Quick-fire questions:

What the best part of the job?

It is absolutely seeing something that no one ever has before. When our gear comes back up to the surface we pop out a memory card and there are hours of footage from a place no one has ever seen before: that’s exciting. But, when something spectacular swims into view, something that five minutes ago we didn’t even know existed. It’s hard to describe that feeling.

What’s your favourite underwater creature?

I’m fascinated by the hadal snailfish and how the deepest living fish aren’t anything like the stereotypes of a deep-sea fish. This was my first species description as lead author and has such a big impact on our understanding of hadal snailfish, so this little blue fish is the current winner.

Is there a species that you would like to encounter but haven’t?

So many. A lot of the abyssal fishes live shallower as juveniles. I’d love to swim with some of the species I study, even if it’s only the babies a few centimetres long.

Have you experienced swimming with sharks?

A few times. Nothing too big and scary while out scuba diving. I did get to swim with some big sand tigers at Deep Sea World in Edinburgh.

Do you ever get sea sick?

Very! It takes me about 3 days to find my sea-legs.

How long have you worked at Newcastle University?

I think it is coming up to six years. Although for the last couple of years we have spun out of Newcastle University as our own consultancy, Armatus Oceanic. Providing deep-sea technology and science advice as well as communicating deep-sea science through projects like The Deep-Sea Podcast.

What is your favourite place to visit and why?

I have been lucky enough to travel a lot with this work. I’ve worked in New Zealand, in the Kermadec Trench and I really enjoyed it there.

What’s next for you?

To continue to develop our consultancy and try new things in science communication. It’s really hard to find accurate deep-sea information as an interested member of the public. The deep-sea has been type-cast and is not presented fairly, even in reputable places. We try to share it as it really is, while still having some fun.

Where do you see yourself in ten years’ time?

I’m not sure what I’m doing next week! I would hope that I am still seeing things that people have never seen before and getting to share my findings with the world.

You might also like

- listen to Dr Thom Linley’s and Armatus Oceanic’s Deep-Sea Podcast

- read the research paper about this discovery: Independent radiation of snailfishes into the hadal zone confirmed by Paraliparis selti

- find out more about how our work is making new discoveries