Professor Roy Taylor on discovering the cause of Type 2 diabetes

30 October 2023 | By: Professor Roy Taylor | 8 min read

Once considered an irreversible condition that worsens with time, research at Newcastle University has shattered conventional beliefs about Type 2 diabetes.

Professor Roy Taylor's pioneering discoveries have been accepted by the NHS - signifying more than just a scientific breakthrough, but marking a shift in how we perceive and treat Type 2 diabetes (T2D). His findings - demonstrating the reversibility of T2D - have become a beacon of hope for thousands, empowering patients to transform their lives. Here, he shares with us what his research has involved.

Contents:

-

What happens to food after you eat?

-

The role of the Newcastle Magnetic Resonance Centre

-

Testing the Hypothesis: Counterpoint study

-

The Personal Fat Threshold Hypothesis

-

Rolling out the weight loss method in Primary Care: DiRECT

-

But how about T2D in people who are not overweight?

-

The ReTUNE study: Testing the second hypothesis

-

The ReTUNE study: Additional findings

-

The NHS England Path to Remission Programme

What happens to food after you eat?

Many scientific breakthroughs start with a simple question. What happens to food after you eat? When I moved to Newcastle as a junior doctor in 1979, we simply did not know.

Using newly developed advance magnetic resonance methods, we found that people destined to get Type 2 diabetes (T2D) stored almost none of their meal carbohydrate as glycogen in muscle - we then showed that fat levels in the liver were high in such people. But all this research was done using MR scanners in other universities, and to take the research forwards, Newcastle University needed a dedicated MR Centre.

The role of the Newcastle Magnetic Resonance Centre

Pictured above, Newcastle Magnetic Resonance Centre opened in 2006 and is situated on the Health Innovation Neighbourhood.

Evoking enthusiasm for such a Magnetic Resonance Centre in Newcastle was the next task. It took from 2000 to 2004 to raise the necessary £5.2 million. A fine new building containing a 3 Tesla MR scanner opened in 2006 on what is now the Health Innovation Neighbourhood.

But by one of those quirks of fate, the final piece of the jigsaw of what causes T2D occurred to me just 3 months after the Newcastle MR Centre opened. When people with T2D were unable to eat after bariatric surgery, their blood sugar levels fell. This was widely thought to have other explanations, but to me, it all fitted together: over a period of years, people unable to store glucose normally after eating would steadily increase the level of fat in the liver with a knock-on increase in fat on the pancreas.

I called this my Twin Cycle Hypothesis, publishing this in 2008.

In this, I postulated that T2D might be caused in pre-disposed people taking in a little too much food daily, causing liver fat to build up with the release of too much glucose from the liver. The Newcastle MR Centre allowed me and my team of medics and scientists to test these ideas.

Testing the Hypothesis: Counterpoint study

‘Counterpoint’ refers to COUNTERing the Pancreatic inhibition of Insulin secretion by Triglyceride (with a passing nod to my favourite Aldous Huxley novel, Point Counterpoint).

The design was simple: If the hypothesis was correct, I could test it to destruction by removing the driving factor of excess liver fat, so if glucose levels did not return to normal it was wrong. The charity, Diabetes UK, had the courage to fund this speculative idea.

The big challenge was devising a way to obtain what I calculated would have to be 15kg of weight loss. It had to be all within 8 weeks because the period of grant support was short. From listening to my patients describe the difficulties in losing weight over decades, I knew the two main problems had to be avoided: hunger, and the cumulative strain of deciding what and how much to eat every day.

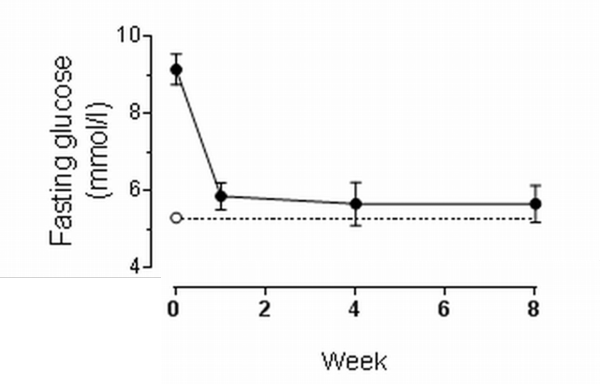

That led to us using one 200-calorie liquid meal (the participants’ only choice being the flavour) at three mealtimes per day, plus salads or leafy vegetables. Somewhat to my surprise, it was highly effective and the participants actually liked it - so much so, that they lost an average of 15.3kg in 8 weeks. As can be seen in this diagram, their fasting blood glucose dropped to near-normal levels:

This graph shows the dramatic fall in blood glucose (sugar) levels before breakfast only one week after stopping glucose-lowering medications and starting the 800 calories per day diet. The dotted line shows glucose levels in a matched non-diabetic group.

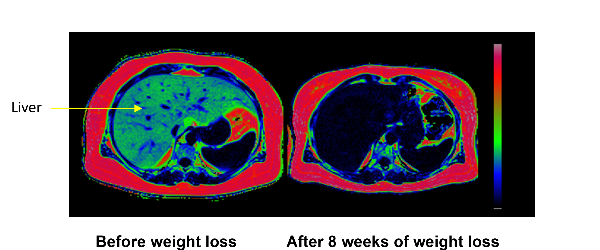

The team - with special mention of Dr EeLin Lim, clinical research fellow, and Dr Kieren Hollingsworth, MR physicist - measured each of the mechanisms postulated in the Twin Cycle Hypothesis. To my astonishment, they were all as predicted. The amount of fat in the liver of these people with ordinary T2D was shocking – and disappeared remarkably with the weight loss, as shown in these MRI scans:

Every pixel in these images is colour-coded for the percentage of fat at that point in space. The fatty tissue under the skin is red, and black areas show very little fat. The arrow points to the liver which was 36% fat before weight loss and only 2% after weight loss.

Because of this decrease in liver fat, the liver stopped pouring out glucose and fat, and the cells making insulin in the pancreas were released from the inhibitory effect of the excess fat. Thus, the Twin Cycle Hypothesis was proven! The resulting paper in the main European diabetes journal, Diabetologia, became the journal’s most highly cited paper for the next two years. But this was just the beginning. Would the reversal of the underlying processes last once people returned to normal eating and keeping weight steady?

That was tested in the next study, Counterbalance (Counteracting BetA cell failure by Long term Action to Normalize Calorie intakE) which showed that all the underlying mechanisms remained normal for 6 months of normal eating.

In addition, this study addressed the question of whether people with a long duration of T2D could also return to normal. The sooner, the better! After 10 years, the chance of achieving remission was very much lower.

The Personal Fat Threshold Hypothesis

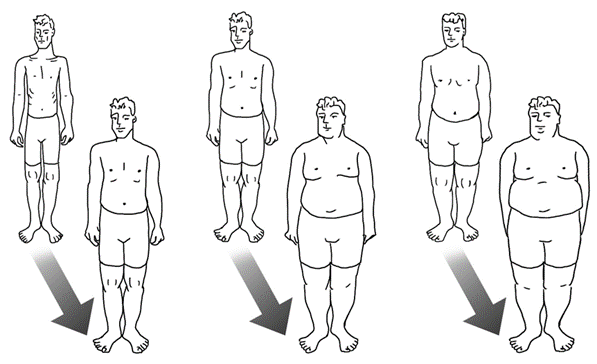

Ingrained in medical thinking is the concept that T2D is caused by obesity. ‘Obesity’ is defined from population data as a BMI above 30kg/m2. It seemed that T2D only developed when a person became heavier than they personally could tolerate.

But throughout the Counterpoint and Counterbalance studies, the response to 15kg weight loss was the same at both ends of the spectrum of body mass index tested – from 27 to 45kg/m2. The reason appeared to be that fat is entirely safe when stored under the skin, but simple observation suggested that the capacity of this ‘subcutaneous’ compartment was genetically determined. So, each individual would have a Personal Fat Threshold which, if exceeded, may lead to fat being left inside the important organs – in particular, the liver and pancreas.

This image helps us understand the individual. The three 45-year-old men in the front row all have Type 2 diabetes. How can this be if it is simply caused by excess fat? We must consider each individual separately, not compare between them. The back row shows the same men when they were 25 years old. Each has put on a similar percentage weight, and all weight gain in adult life is gain of fat. The man on the left simply has a lower threshold of tolerance for the absolute amount of fat in the body. A few years later, researchers at Oxford University showed that the capacity of safe storage of fat (under the skin) was genetically determined by 53 separate genes.

To publish a well-argued hypothesis, I sought the help of Prof Rury Holman of Oxford University, as he held the database of the most famous study in the history of T2D research.

Over one-third (36%) of the people in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study had a ‘normal’ BMI - that is difficult for modern-day doctors to comprehend - but at the time of recruitment (between 1977-1991), only 7% of people in the population of the UK were obese. And yet this was the study that told us most of what we know about T2D: a disease currently believed to be caused by obesity. Our rethink was overdue.

Rury and I published the Personal Fat Hypothesis in 2015 to draw attention to this matter. Conducting a formal study to test the hypothesis had to wait until more pressing research had been finished.

Rolling out the weight loss method in Primary Care: DiRECT

A very practical question had to be answered. Could the method of reversing the underlying processes of T2D be used in routine Primary Care, where most people with T2D are managed? Diabetes UK was willing to consider extending its grant support for this people-centred question.

My colleague, Prof Mike Lean of Glasgow University, had applied the method developed in Counterpoint to find out if it could be used in Primary Care to treat obesity, and had developed a routine of training primary care nurses or dietitians in how to use the diet. Diabetes UK suggested that Mike and I collaborated to run a large study, and the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) was born. It is the largest study funded by Diabetes UK.

DiRECT was a simple, randomised study in Primary Care to compare the rapid weight loss method in T2D with another group, who were managed according to best practice guidelines. Each practice nurse (or dietitian in Scotland) was provided with a structured 8 hours of training. After one year, almost half of all the 149 people in the weight loss group were free of their diabetes and off all diabetes medications, having lost an average of 10kg. After two years some weight regain had occurred, but still over one-third of participants were free of diabetes.

However, we were able to confirm in the Newcastle cohort, that the underlying mechanisms causing the disease were reversed - exactly as already shown in our earlier studies - when supervised by nurses out in the real world. Even more excitingly, we showed that the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas recovered very gradually over a one-year period. Therefore concluding that the previous belief that these cells had died, was wrong – they were merely inhibited by the excess of fat and sugar.

But how about T2D in people who are not overweight?

This question had come sharply into focus as soon as the Counterpoint results were published in 2011. Following this, I received an extraordinary influx of emails from people with diabetes, requesting how-to-do-it information which led to the hasty construction of information available on the Newcastle University website.

Then came a wave of emails either reporting the outcome of following the ‘Newcastle diet’ or reporting upon what happened when people discussed this with their diabetes nurse or GP. Together with Dr Sarah Steven - the brilliant doctor who conducted the Counterbalance study - I published an analysis of this real-world experience in 2014.

But by far the most anguished emails came from people reporting that they had been told they must not lose weight as their present body mass index was already in the normal range, and weight loss would be unhealthy.

Many of these ‘normal’ weight people decided to take matters into their own hands and discovered that they too could reverse their diabetes by weight loss. But we needed a formal study to test the Personal Fat Threshold Hypothesis - and so in 2018, Diabetes UK funded a research grant to carry this out.

The ReTUNE study: Testing the second hypothesis

The ReTUNE study - Reversal of Type 2 diabetes Upon Normalisation of Energy intake in non-obese people – was designed to test the Personal Fat Threshold Hypothesis. Would T2D return to normal with weight loss in a group of people with lower BMI? And how much weight loss was required to cross the threshold?

The answers were clear.

Yes, weight loss did normalise all the underlying mechanisms exactly as it did in heavier people. It was discovered that weight loss of 6.5% was required to cross the threshold on average for this group. This led us to decide that doctors need to change their practice: if a person has ordinary T2D, then they have become too heavy for their own body (or genetic makeup); weight loss has to be the first therapeutic move by whatever means suitable for the individual; only if this fails for whatever reason should there be a resort to drugs.

It will take a long time for this to be accepted into routine practice, but the hard evidence is available.

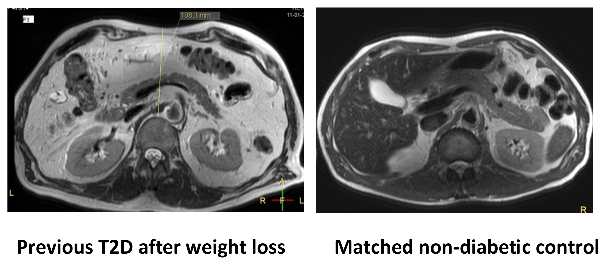

The results of the ReTUNE study were remarkable. At baseline, these apparently slim people had three times as much fat inside their livers compared to the weight-matched non-diabetic control group. As a result of the study, liver fat decreased rapidly and 70% of people returned to the non-diabetic state having stopped all diabetes medications. ‘Looking’ inside these research participants using MRI gives an idea of how clogged up with fat their bodies had become – without showing as readily visible fat under the skin.

Compared to the group without T2D, those with T2D had excess fat inside the tummy cavity even after weight loss (although no longer any excess inside the liver and pancreas). Unlike most people of their weight, the ex-diabetic group had been unable to store the fat safely under the skin.

The ReTUNE study: Additional findings

There was another important result from ReTUNE. Because we thought that some rare forms of diabetes may be more common in people of lower BMI, we carried out careful testing of all 24 people in this study. This was done at the national testing Centre in Exeter. We had to be sure that we were studying genuine T2D, not conditions caused by other factors.

Two people turned out to have monogenic diabetes, a rare genetic reason for glucose levels to be high. Two others had a slow onset form of Type 1 diabetes. From this, we learnt that doctors need to bear in mind that some of the people who do not return to normal after weight loss may have a rarer type of diabetes than the vast majority.

The NHS England Path to Remission Programme

The health benefits and economic advantages of helping large numbers of people escape from T2D resulted in a pilot scheme to establish whether the research findings could be reproduced on a large scale. They could, and the scheme transitioned to being a full national programme in 2022. It is still being rolled out across the country, but success in the pilot scheme saw several thousand people achieve 10kg weight loss - a level expected to bring about remission in 30-40% of participants in one year.

By establishing the underlying cause of Type 2 diabetes it has been possible to improve the health of many people. Cutting-edge MR techniques, combined with good old-fashioned physiological research and clinical insight, have transformed the understanding and management of Type 2 diabetes.

You might also like:

- learn more about Professor Roy Taylor, his research, teaching and publications

- discover the Newcastle Magnetic Resonance Centre and the diabetes research we do there

- find out more information about reversing Type 2 diabetes and ongoing remission

- explore further insights into Professor Roy Taylor’s work on the FROM Blog

- learn about Professor Roy Taylor's 2024 Rank Prize for Nutrition win

- listen to Professor Roy Taylor's Type 2 Diabetes Masterclass on the podcast, The Proof

.