Mobilising data to tackle species extinction

9 April 2021 | By: Newcastle University | 4 min read-1.jpg)

Human-driven changes in biodiversity and the consequences they have for economies, societies and natural services are increasingly the focus of global environmental policy.

It is now accepted that biological diversity is not only the foundation of a resilient environment, but that it also underpins robust societies and economic development.

The Sustainable Development Goals that the world’s governments agreed in 2015 reflect just how integral the environment is to healthy societies and sustainable economic development.

Despite this understanding, we know that species, and the habitats that they make up, are in trouble.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, which is widely regarded as the authoritative assessment of the conservation status of species, lists some 35,000 species at risk of extinction, out of about 130,000 that have been assessed.

We know that conservation targeted at species can and does work, but the challenge is simply the number of species that need to see a reduction in the threats that they face: we cannot tackle all those threatened species one at a time.

Taking a strategic approach

So, how can we act more strategically, to find ways of identifying policies and actions that can have the biggest impact on reducing the risk of extinction facing species?

Part of the answer lies in understanding which threats have the biggest impact on the extinction risk of species, and part lies in understanding where those threats have their biggest impact: in other words, places where there is a lot of extinction risk.

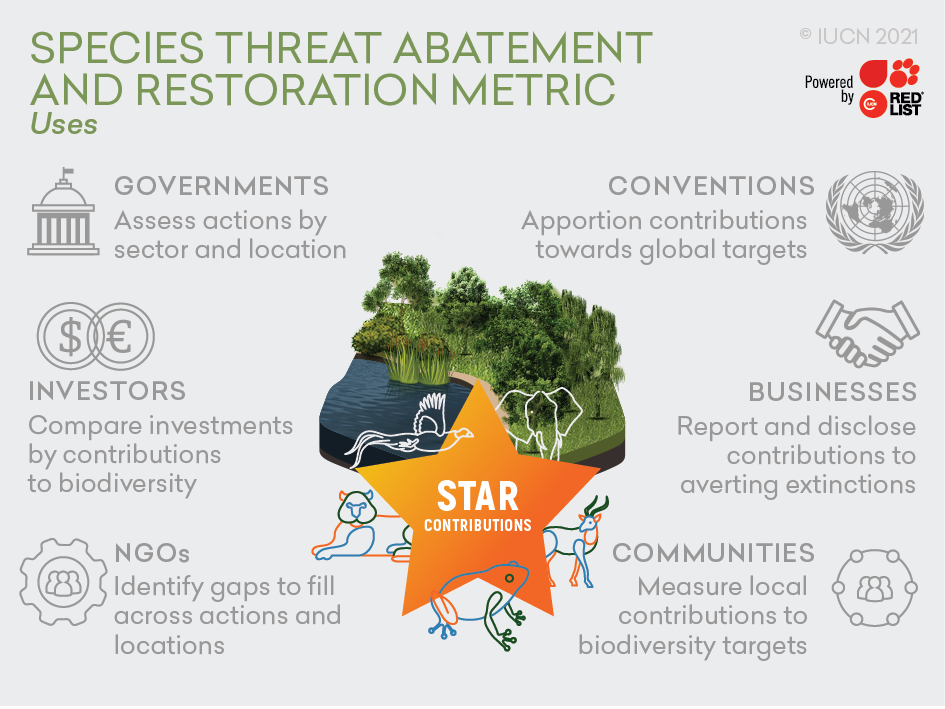

Getting this right is becoming increasingly important to governments, businesses, NGOs and others, many of which have targets and programmes to reduce the negative impacts of human activities on nature and drive recovery.

Putting in place a way to do this is a significant challenge, however, both in terms of getting the approach right and in terms of analysing data on how threatened species are, where they are found and what pressures they face.

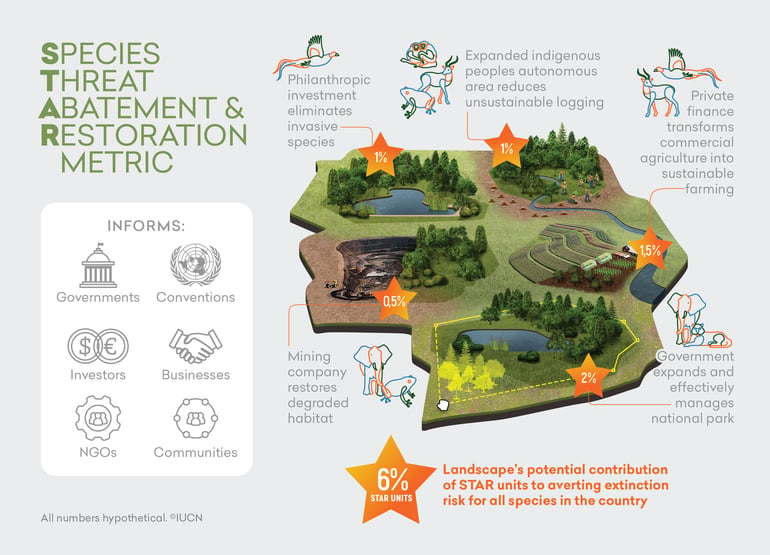

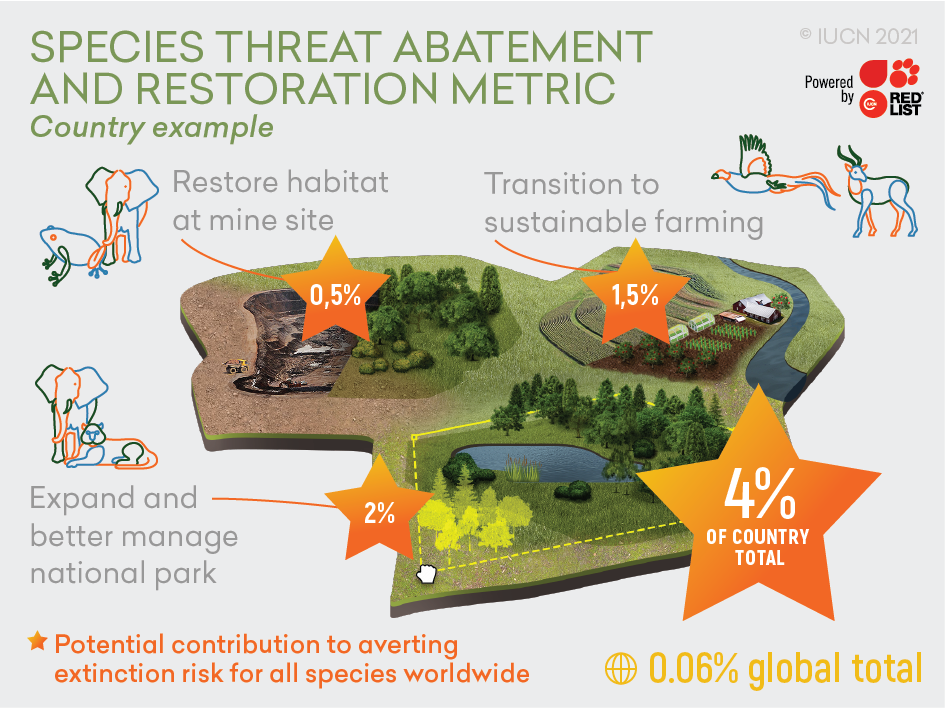

What STAR does, in a nutshell, is to provide an overall measure of species at risk of extinction in a particular place, whether this is the whole world, a country, landscape, protected area, or the places where a particular company or investment bank operates.

The Species Threat Abatement and Restoration (STAR) metric addresses these challenges for the first time, providing a science-based approach for understanding how and where to reduce species extinction risk.

What is the STAR metric?

STAR was developed by a collaboration of some 85 authors from more than 60 institutions across six continents. Authors come from a range of backgrounds, including universities and research institutes, businesses, science policy and intergovernmental organisations, NGOs and government agencies.

The development of the metric was led by Newcastle University, together with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an intergovernmental organisation that has Observer status at the UN General Assembly. Dr Louise Mair headed up the work carried out here at Newcastle University.

What STAR does, in a nutshell, is to provide an overall measure of species at risk of extinction in a particular place, whether this is the whole world, a country, landscape, protected area, or the places where a particular company or investment bank operates.

This is based on the species that occur there, and how threatened each species is, with species that are more threatened weighted more highly than those that are less threatened with extinction.

The IUCN Red List contains this information for a range of species groups, and STAR has been developed using the well documented groups: birds, mammals and amphibians. The IUCN Red List also contains information on the threats facing species on the list. This allows analysis of the threats facing species in a particular place: whether that’s the world, a country, a site or anywhere in between.

This therefore allows assessments of which places have the highest overall extinction risk and which threats are contributing to the overall extinction risk in a place.

Understanding the metric in practice

A couple of examples may help to illustrate this.

Although all countries can and should contribute to the reduction of global species’ risk of extinction, the contributions vary between countries. The five highest scoring countries have the potential to reduce global extinction risk by 31%. These are Indonesia, Colombia, Mexico, Madagascar and Brazil.

Globally, species extinction risk could be reduced by 25% by tackling threats from crop agriculture, and a further 16% by tackling threats from logging and wood harvesting.

The relative importance of different threats varies among countries.

For example, in New Zealand, the threat from invasive species accounts for 68% of the national STAR score, whereas in Namibia, 20% of the national score is contributed by the threat from hunting and collecting terrestrial animals, and a further 14% by threats from livestock farming and ranching.

STAR provides an approach that allows us to tackle species extinction risk, without the need to develop species-by-species action plans.

Potential impact

The development of the STAR metric is very timely, as the Convention on Biological Diversity continues negotiations of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, which will provide the context for governance of the world’s biodiversity over the next decade and beyond.

Crucially, STAR links:

Outcome Goals - the proposed outcomes for species that countries are considering

with

Action Targets - the actions that need to be implemented to achieve those goals

STAR does, however, also have much broader potential. During its development, we have presented and discussed STAR in a number of settings, including:

- UN High Level Political Forum event on science-based targets

- World Bank’s Environment, Natural Resources and Blue Economy Global Practice

- Coalition for Private Investment in Conservation

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in relation to their EX-Ante Carbon Balance Tool

STAR provides an approach that allows us to tackle species extinction risk, without the need to develop species-by-species action plans.

Instead, STAR tackles the pressures that are causing their declines.

This allows us to set ambitious but realistic, science-based targets for species conservation, by understanding the policy and management changes that need to happen in order to reduce species extinction risk in a particular place.

These places could be countries, landscapes, sites or a range of places where a company or financial investor operates.

This diversity of places means that there is great potential to engage diverse actors in conservation by identifying responsibilities and potential positive impacts, measuring everyone’s contributions towards the post-2020 framework.

The development of STAR was part-funded by the Luc Hoffmann Institute, Vulcan, Synchronicity Earth and the Global Environment Facility, as well as support from the Conservation International GEF Project Agency.

Find out more

If you'd like to find out more about the STAR tool, get in touch with Dr Louise Mair or the team at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). For general or technical inquiries about STAR, please contact star@iucn.org or if you're interested in applying STAR for commercial uses, please contact star@ibat-alliance.org

Further reading

- about the STAR metric

- the research paper

- mapping the biggest threats to endangered species in your local area

- measuring contributions towards biodiversity targets

We're making a difference to the world through research. Sign up for our newsletter below to keep up to date with our latest findings.