How we're helping diagnose unexplained kidney disease

25 March 2024 | By: Newcastle University | 3 min read

Scientists at Newcastle University have identified a new method of analysing genomic data in a major discovery that means patients with unexplained kidney failure are finally getting a diagnosis.

Read on to discover how our experts have worked with data from Genomics England 100,000 Genomes Project to establish a diagnosis, and what this means for patients and their families.

Identifying a missing gene

There are numerous reasons for kidney failure, which left untreated can be life-threatening. Often, patients do not get a precise diagnosis, which can make their best course of treatment unclear.

Research published in Genetics in Medicine Open has revealed that for these patients, areas in their genome are missing. They are not detected as faulty when using routine genetic pipelines to analyse data. This missing gene has now been identified and mutations within it have been found. This means scientists have been able to classify this as NPHP1-related kidney failure.

New genomic approach

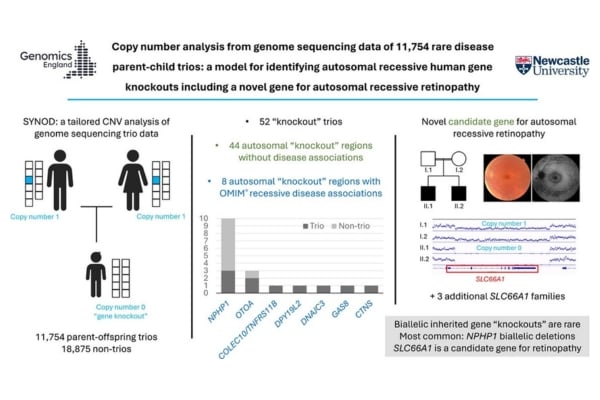

In the study, experts reviewed genetic sequencing data from 959 patients with advanced kidney disease, where a total of 11 patients were identified as having a deleted region genome, leading to a complete loss of a kidney gene. This had previously been undetectable.

The new approach was also used to examine genomic data from 11,754 cases to make new genetic diagnoses of 10 other UK patients with unexplained deafness and blindness, that had previously been genetically unexplained.

Graphical abstract of the study. Credit: Genetics in Medicine Open DOI: (10.1016/j.gimo.2024.101834)

Professor John Sayer, Deputy Dean of Biosciences at Newcastle University and consultant nephrologist at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, who led the study said:

“Our new genomic methods and their results has huge implications for the patients and families with kidney failure who were previously genetically unsolved.

“What we are now able to do is give some patients a precise diagnosis, which allows their investigations, treatment and management to be tailored to their needs for the best possible outcomes.”

The work, co-funded by Kidney Research UK and the Northern Counties Kidney Research Fund, was possible through the Genomics England 100,000 Genomes Project, where Professor Sayer has been instrumental in the North East’s success of this project.

The Bingham Family Journey to Genetic Diagnosis

The Bingham family have three members affected by kidney disease. The family are part of the Genomics England 100,000 Genomes project and were one of the families identified as having the gene deletion, NPHP1-related kidney failure. Siblings Noah, 23, and Ariel, 19, have both had kidney transplants and their younger brother, Casper, 15, has been diagnosed with kidney disease.

The Bingham family

The Bingham family

Mum Sarah shares their experiences, and why having an official diagnosis is so important:

“At 11 years of age my middle child, Ariel, was admitted to hospital with stomach pains, which turned out to be of no significance, however, her bloods revealed a substantial reduction in kidney function. She was sent for various tests and scans, and last of all, a kidney biopsy. The kidney biopsy revealed chronic kidney damage but there were no answers as to why, or what was causing the issue.

“Given her young age, it was thought that the condition may be genetic. Ariel was given a possible diagnosis of ‘a type of nephronophthisis’, and we as a family were invited to take part in the Genomics England 100,000 Genomes Project. We were told that we shouldn’t expect to get any specific answers relating to her condition, or a clearer diagnosis for a good few years.

"It was explained that trying to find the gene responsible was like trying to find a specific word within a set of hundreds of volumes of encyclopaedias.

“My youngest child, Casper, was tested in terms of kidney function, which appeared stable at this point. Because there was no specific gene to look for, his kidney function was the only measure that could be used. We were hopeful that he was not affected by the same condition, and he was monitored annually. My eldest child, Noah, who was 16 years of age by this point, was assumed to be ‘in the clear,’ as he did not appear to be showing any symptoms.

“Just three years later however, Noah went suddenly and unexpectedly into kidney failure. It seemed undisputable that he did, in fact, have the same condition as Ariel, and his bloods were taken for genetic analysis also.

“The day we went into national lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic, I received a call from Professor Sayer. He told me that they had an official molecular genetic diagnosis.

"He said that having Noah’s DNA to compare with Ariel’s DNA had made the search for the gene responsible for their kidney failure easier. It was like cutting down the encyclopaedias to a couple of chapters in one volume.

“The genetic diagnosis in Noah and Ariel then allowed Casper’s DNA to be examined, to see for certain if he was affected or not. Unfortunately, he was.

“As a parent, having an official diagnosis, however bleak, was very important. When nobody is able to explain why your child is ill, it is very unsettling, with no means of clarifying what might happen in the future. The diagnosis has meant that we have been able to prepare ourselves well in advance for Casper’s future.

“The knowledge that he will go into kidney failure and will need a transplant, though overwhelming at times, has meant we can arrange the support he needs and help him prepare for surgery and treatments well before they are necessary. There is a chance he will be able to receive a pre-emptive transplant, avoiding the need for dialysis.

“I am aware there is intense research into possible new treatments for NPHP1 deletion but there is nothing clinically available yet. I hope that a potential treatment can be found quickly to help families like ours who are affected by nephronophthisis.”

Further study

The Newcastle team are now working with cell lines taken from patients to study the disease process in more detail and to test potential treatments.

The hope is to provide a proper diagnosis for many more families in the future.

You might also like

- read the paper: Copy number analysis from genome sequencing data of 11,754 rare disease parent-child trios: a model for identifying autosomal recessive human gene knockouts including a novel gene for autosomal recessive retinopathy. John Sayer et al. Genetics in Medicine Open. DOI: 10.1016/j.gimo.2024.101834

- read the press release

- learn more about Prof John Sayer, Deputy Dean of Biosciences and Clinical Professor in Renal Medicine

- explore our Biosciences Institute and our interdisciplinary, cutting-edge research

- Newcastle University and Newcastle Hospitals are both part of Newcastle Health Innovation Partners (NHIP). NHIP is one of eight prestigious Academic Health Science Centres (AHSCs) across the UK, bringing together partners to deliver excellence in research, health education and patient care.

- find out more about the 100,000 Genomes Project