Helping more girls complete basic education in Kenya

12 July 2023 | By: Dr Ann Njeri, PDRA (Extragalactic Astrophysics) | 4 min read

Why do so many girls in rural Kenya not complete their education?

Ann Njeri, PDRA (Extragalactic Astrophysics) in the School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics, explains why this happens and how to make change.

Contents:

- Girls and the education problem

- The facts: girls in education in Kenya

- Why don't girls in rural Kenya complete their education?

- Poverty and a lack of opportunity

- ‘Elimisha Msichana, Elimisha Jamii'

- But what more can be done?

Girls and the education problem

In rural Kenya, almost an equal number of boys and girls sit for the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education, which marks the end of primary education and the beginning of secondary education.

However, only a small percentage of girls finish secondary/high school and sit for the Kenya Certificate for Secondary Education (KCSE). Even fewer proceed beyond secondary into tertiary education.

Although the majority of girls in Kenya complete primary education, few fully complete their secondary education because of several socio-economic issues, such as teenage pregnancies, early marriages, poverty and lack of mentorship. Addressing the issue of gender disparity and equality in education is critically important for social and economic growth within these regions.

The facts: girls in education in Kenya

Only 18% of Kenyan women aged 25+ have completed secondary education with ~49% of the female youth (15-24) population considered illiterate.

86.5% of girls aged 9-13 years live in rural Kenya with 80.8% of them attending primary school but only 14.3% enrolling for secondary.

68.6 % of girls in the same age bracket in urban areas complete primary education with 27.8% enrolling for secondary education.

About 20% of female pupils who sat for their KCPE in 2015 failed to enrol in secondary schools in 2016.

In 2009, out of the total 762,569 children of school-going age out of primary school, close to 400,000 were girls.

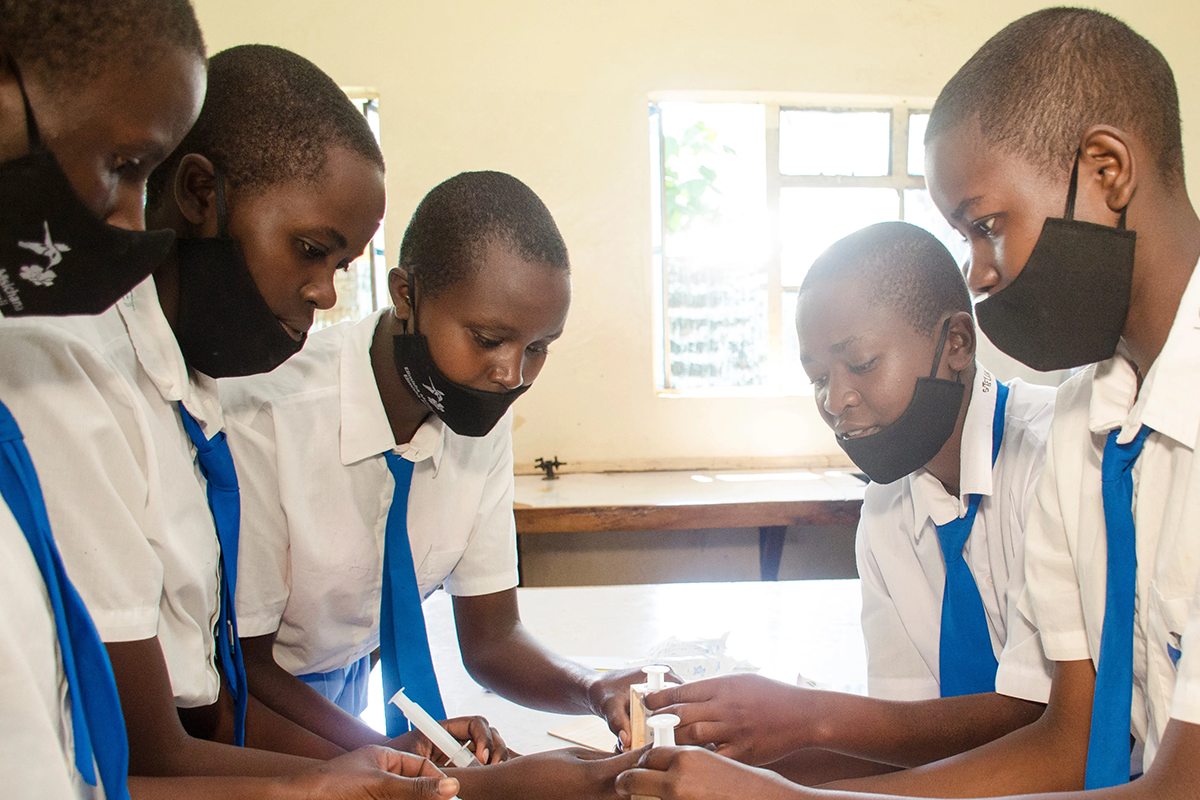

Photo credit: Dr Ann Njeri

Why don’t girls in rural Kenya complete their education?

Most girls in rural areas in Kenya do not complete secondary education due to several socio-economic issues such as teenage pregnancies, early marriages, poverty and lack of mentorship.

As of 2019, Kenya had the third highest teen pregnancy rate in the world at 82 births per 1,000 births with approximately 25% of Kenyan women giving birth by the age of 18 and nearly 50% by the age of 20. The situation is even worse in rural areas where most adolescent girls already have children by the age of 18. Out of 13,000 teenage girls who drop out of school annually due to early pregnancies, only half ever go back.

An associated challenge for girls’ continuation in education is the high rate of early marriages. Roughly one in every three girls in developing countries is married before the age of 18 and one in nine is married before the age of 15. The rates stand at 37% in Sub-saharan Africa with Kenya having the 20th highest number of child brides (527,000) in the world in 2014.

Poverty and a lack of opportunity

Kenya is grappling with high levels of poverty and a vast wealth gap between the poor and the ultra-rich, leading to inequalities.

As of 2015, 36.2% of the population was still living below the international poverty line. Poverty is the biggest enemy of education as the poorest students are more likely to fall victim to health, lifestyle and economic issues that compound to impede their access to school. These issues create an endless cycle of poverty, which impacts students, their families and the wider community.

Additionally, rural areas lack outreach, leadership and mentorship programmes for young schoolgirls. Existing mentorship schemes are mainly aimed at girls already in secondary education, thus missing out on the primary-to-secondary transition where school dropout rates are high. Therefore students in rural areas lack mentors that they can relate to and look up to for motivation and inspiration. Most of them also have no exposure to the outside world and are confined to their small villages. This results in most pupils, especially girls, lacking the desire and motivation to continue into and complete secondary education.

‘Elimisha Msichana, Elimisha Jamii'

- Mentorship and outreach: EMEJA is mentoring and supporting girls as they complete primary education. This is achieved by visiting primary schools, engaging the community (the pupils, their teachers and parents) in roundtable discussions addressing the socio-economic issues that may prevent girls from completing secondary education and focusing on positive actions that the community can implement in tackling these challenges. Each girl in the final year is paired with an EMEJA mentor.

- Tracking and long-term monitoring: EMEJA mentors keep track of their mentees throughout secondary school through face-to-face or phone calls every three to four months. Roughly one third of the girls we are currently mentoring are young mothers who have one or two children.

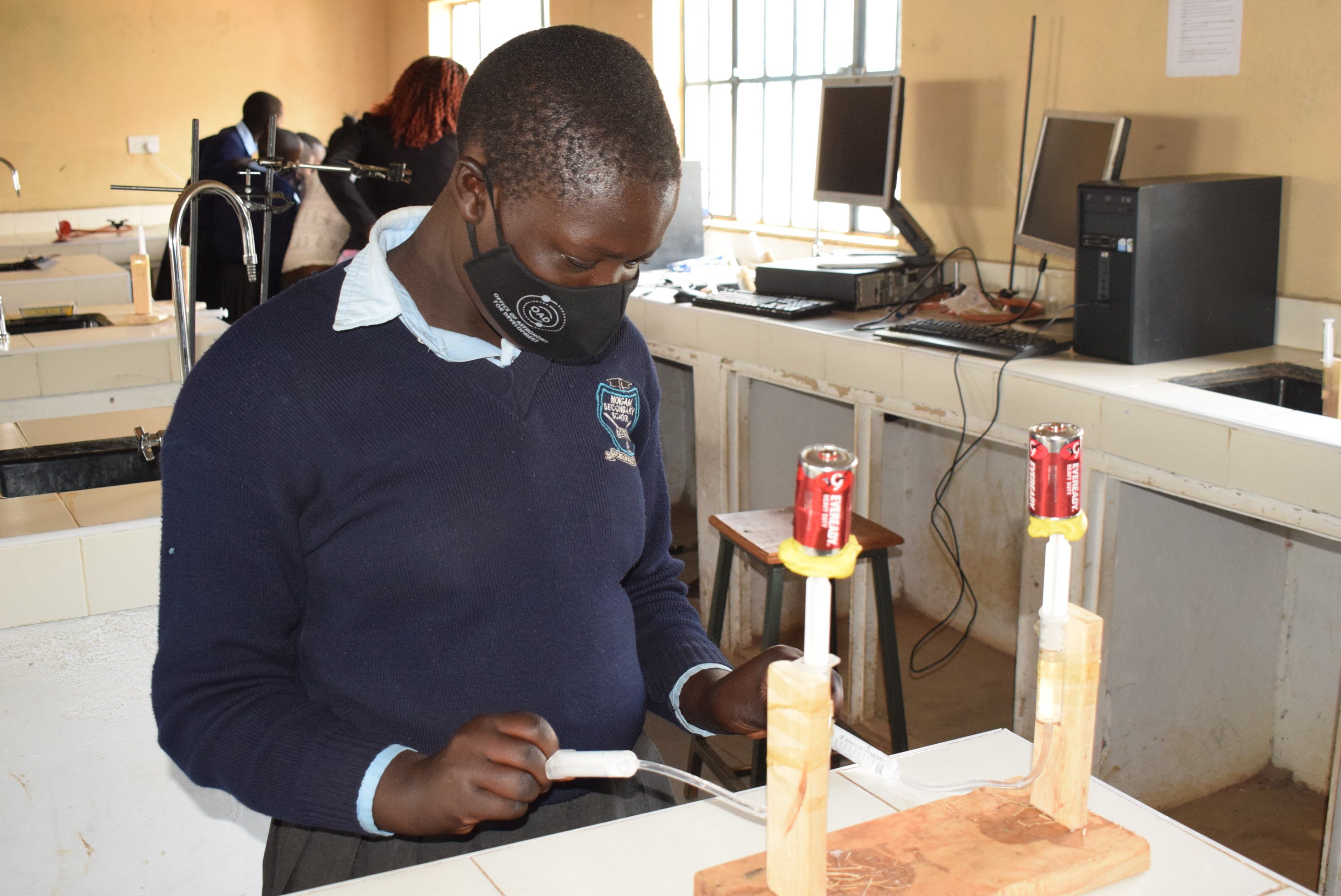

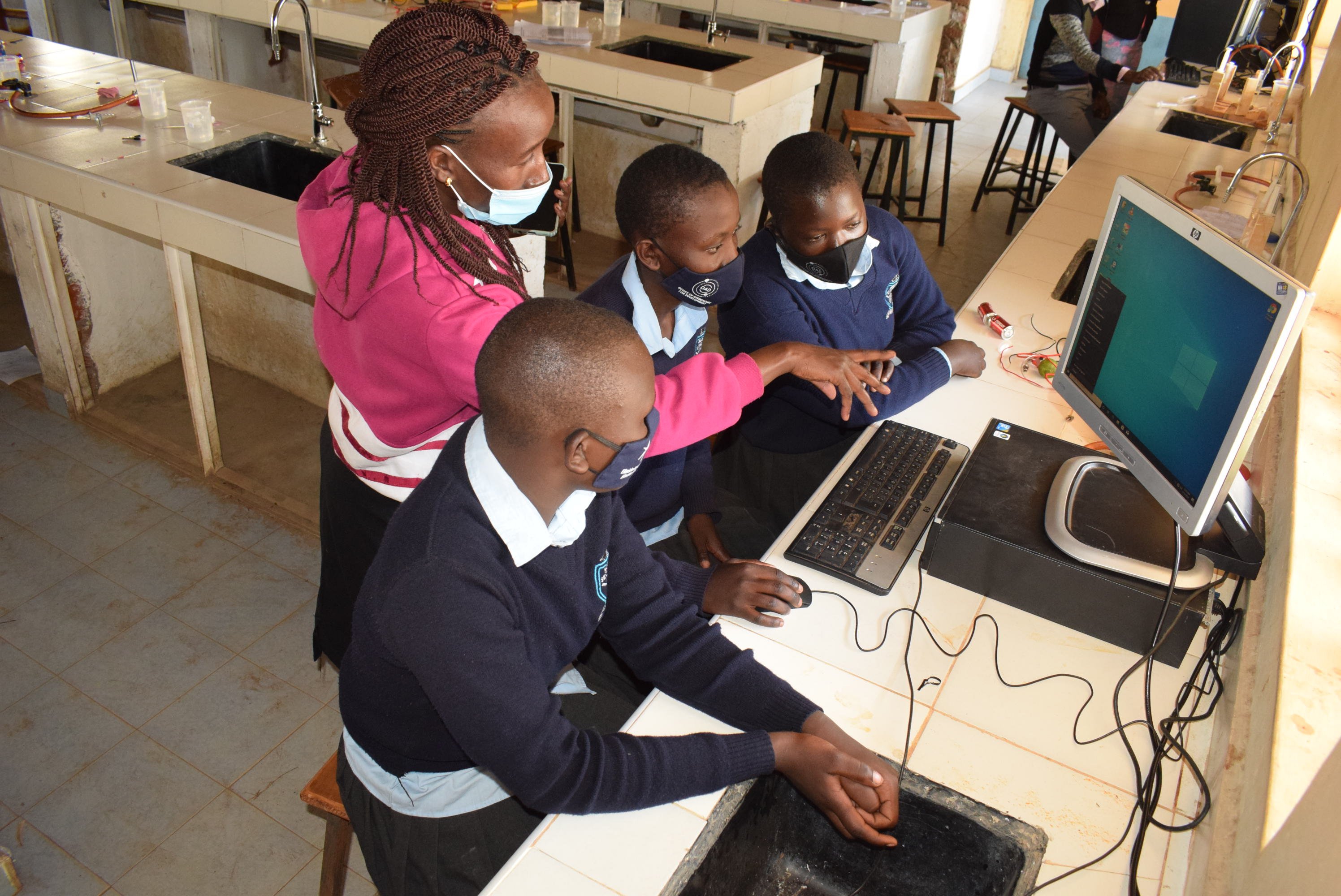

- Astro-STEM workshops and mentorship: The key objectives are: to change misconceptions about STEM subjects among schoolgirls and facilitate early participation of girls in sciences; improve grades in STEM; increase the number of girls selecting Physics in Year 3-4 and sitting for the Physics KCSE, and; increase enrolment of girls in STEM courses at the tertiary level. Astro-STEM is also providing the target schools with some laboratory equipment and computers.

- EMEJA tuition fee scholarship: Lack of school fees is key reason for school discontinuation in rural areas and disproportionately affects girls. Therefore, we are working with rural secondary schools to provide tuition fee sponsorship to some of the poorest girls who can’t afford to enrol in secondary education.

Photo credit: Dr Ann Njeri

But what more can be done?

In the long run, we will not only be addressing the gender inequality Sustainable Development Goals but also all the other related and intertwined SDGs, such as ‘no poverty’, ‘zero hunger’, ‘good health and wellbeing’, ‘quality education’, ‘decent work and economic growth’ and ‘reduced inequalities’.

But we can’t do this alone.

One of the key reasons girls don’t complete secondary education is because of teenage pregnancies and early marriages. EMEJA provides sex advice during our mentorships but the majority of students receive no formal sex education, with only a few receiving advice through counselling services. The few services available mainly exist in urban schools and are inaccessible to rural school children. Basic sex education should be taught to all students in both primary and secondary schools across Kenya.

Additionally, rural schools need to be accessible and provide the basic infrastructure to support students’ learning. This includes things that are taken for granted in more affluent areas, such as well-equipped laboratories or the resources to support extracurricular learning.

Distributing more funding to rural areas could allow for more secondary schools to be built and for existing schools to buy more equipment or renovate their buildings. Increasing the quality and accessibility of secondary schools will have a huge impact on opportunities for the most disadvantaged girls.

More widely, investment in school infrastructure improves the overall quality and accessibility of education for all students. This benefits the whole community and provides students the opportunity to break free from the endless and vicious cycles of poverty and inequality through education.

You might also like:

- Find out more about Dr Ann Njeri, PDRA (Extragalactic Astrophysics) in the School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics

- Discover the work of Elimisha Msichana Elimisha Jamii

- Explore the work done by our School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics

- Find out more about our commitment to supporting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals