Designing our cities to tackle global health issues

5 July 2022 | By: Newcastle University | 4 min read

We live, work, rest and play in them, but during the 20th century our cities weren't planned with humans in mind. Now, Professor of Urban Design for Health, Tim Townshend believes creating healthier cities is within our grasp.

It took a global pandemic to bring into sharp focus the deficiencies in how we’ve created – and lived in – our cities over the last half a century.

During lockdown our homes had to become makeshift classrooms and offices, however this highlighted how cramped and inflexible most UK houses are. As soon as possible we flocked in droves to urban parks, seeking revitalising green spaces. Where and how we lived noticeably impacted our physical, mental and social health.

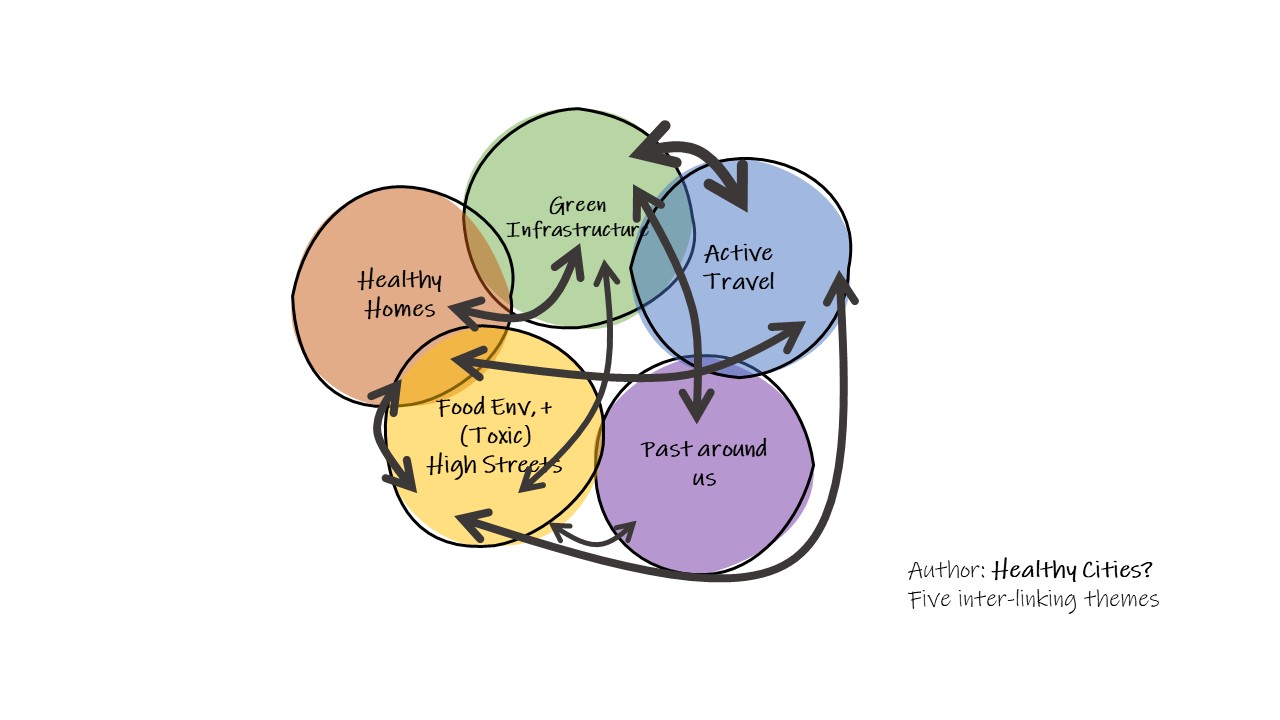

Now, in his book Healthy Cities? Design for Well-being, Prof Townshend explores how our built environment contributes to health and well-being problems, and how the physical design of the places we live in can support, or hinder, healthy lifestyle choices.

In this Q & A, he explains why we must meet the challenge of building for a better life.

Q: What makes a healthy city?

A healthy city provides all citizens with an environment that allows them to thrive and reach their full potential. It is responsive to their needs and should have:

• decent housing - that meets housing space standards, is free from damp and cold, is well-insulated and has access to outside space

• access to public green space - for exercise to support mental health and tackle sedentary lifestyles and obesity, currently a major issue for the NHS

• a good travel infrastructure – allowing citizens to commute to and from work or education

• access to schools within the local area

• suitable shops and services

• healthy food options

People living in a city should have the infrastructure to make healthy lifestyle choices, from recreational and social interactions to mobility and education.

People living in a city should have the infrastructure to make healthy lifestyle choices, from recreational and social interactions to mobility and education.

Q: Why are healthy cities important?

The root of our health and wellbeing is ourselves, but beyond that it’s our lifestyle and our built environment that either constrains or provides opportunities to have a healthier life.

We can also draw parallels with what’s good for human health and what’s good for sustainability – from a biodiversity perspective, a lot of what is good for human health (access to open, green space) also benefits species and wildlife.

Embracing healthy city principles and what the impact could be on the NHS – the potential is enormous.

The Connswater Community Greenway is an urban regeneration project in Northern Ireland. This £40m investment created flood alleviation measures alongside 16kms of cycle tracks and walkways – interventions that not only have a clear safety flood resilience, but also support community cohesion and interactivity, economic development, improvements in public health, and cleaner rivers.

The data analysed, as part of this project, showed that if just 2% of local population became more active, the scheme will pay for itself in cost savings to the NHS. Isn’t that an amazing fact?

Q: How can we improve city life now?

There are some short-term options that can have a dramatic impact almost immediately – for me, nature in cities has high importance.

Look at what London’s Wild West End has done – it aims to improve the physical and environmental quality by giving Londoners access to nature and encouraging wildlife back to the capital.

It’s a scheme to create more green corridors throughout the West End and that can be through the simplest thing – from the greening of unused rooftops to adding planters on lampposts.

Q: What are the biggest barriers to creating healthier cities?

Different issues crop up from city to city, but there are some issues that cut across all.

The seismic shift in the way people shop has created empty shopping centres – shops with rolled down metal shutters that are covered in graffiti. This has a negative impact on wellbeing.

The high cost of land makes convincing housing developers that health is marketable very tricky. Imagine asking a housing developer to forgo building a couple of houses so there’s more green space or room for a bike shed.

The need to bring communities with us on the journey. There’s a great example in my book – the Nationwide Building Society’s first housing development for over 100 years at Oakfield, in Swindon.

What they did here was remarkable. They appointed a Community Organiser who lived in the local community to help understand what residents needed and wanted from a new housing development. That person helped connect ideas and share common goals – how inspiring is that? We’ve got to find more creative ways of listening to communities.

Q: What did Covid-19 teach us about healthy cities?

Following the lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic we are more aware than ever of the impact of our environment on our health and wellbeing.

Covid taught us so many things. Our need for green space is an obvious one, giving the huge increase in use of parks and local beauty spots.

And it showed that some of our housing is not fit for purpose – our house space standards are the smallest in Europe. We’ve got to think about new ways of creating more flexible, multi-purpose homes and outdoor space.

Q: Who should read this book?

I hope it’ll be useful for practitioners, so anyone working in public health, planning to landscape architecture. This book explores many issues but, most importantly, our roles in challenging the status quo and what a difference we could make if we come together to plan and regenerate our cities.

For those in academia - undergraduate and Masters students - I introduce some key topics and further reading. Similarly, there are a lot of useful case studies to support understanding some theories into practise.

Q: What one change would you want to see adopted as an outcome of your book?

Physical greening, there is so much potential to build – retrospectively – green spaces in our cities.

Barbican, London, an example of an urban garden

Q: How can your findings be put into practice?

There are so many powerful and positive lessons to look at, based on principles of innovation, community engagement and a holistic approach to healthy city attributes. We need to look at case studies and assess how applicable they could be to where we live.

In the North East, the Station Master’s Garden, at Whitley Bay is a great example of community gardening. North East Public transport provider, Nexus, allowed the local community to take over an overgrown strip of land south of the town’s station. The community has created vegetable plots, fruit bushes, ponds and story corners for children.

Healthy cities are about involving the community, thinking holistically about needs, and speaking to the right people.

Cities can and should be planned for people in order to optimise the health of their residents and maintain their economic and cultural vibrancy.

Healthy Cities? Design for Well-being is published by Lund Humphries.

Quick fire questions...

Name: Prof Tim Townshend

How long have you worked at Newcastle University: Since 1993!

Research specialism: Links between the built environment and health/well-being

What's next for you? Focussing more on mental wellbeing in my research

Where do you see yourself in ten years' time? Retired and living on a Scottish croft looking after rescue donkeys!

Is there any other city you wish you lived in? Victoria, British Columbia – it’s so beautiful

Countryside or the city? Countryside

Prof Tim Townshend

You might also like...

- Find out more about Prof Tim Townshend, Professor of Urban Design for Health

- Explore our School of Human Architecture, Planning, and Landscape

- Read about the Nationwide Building Society’s first housing development for over 100 years

- Discover Prof Townshend's book: Healthy Cities? Design for Well-being